May 7, 2025

A Note from Pastor April

Dear Friends,

In last week’s Letter of Encouragement, Pastor Jon shared a bit about how the lens of fundamentalism shaped his story. Sunday, he shared more about this lens that has influenced so much of modern Christian practice. Fundamentalism arose largely as a push back to society’s shifting views toward science and evolution.

Interestingly, progressive Christians also had concerns about the growing emphasis on reason and the ways some thinkers in the early 19th century were suggesting that faith had no place in the realm of science. While fundamentalists were worried about losing foundational doctrines of the faith, progressives felt like the lived experiences of people of faith were being diminished.

Early progressive theology sought to show how faith and reason could exist side by side and strengthen one another. The tools of reason could help us understand nuanced context within biblical stories and our own lives, widening our views about how to interpret what was happening.

Experiences of faith invite us into a different kind of knowing — that we are a part of something much bigger than ourselves, a connectional relationship with the divine. Learning to see the complex and nuanced world with more of ourselves ultimately could also help us to see how to build the kind of world where our relationship with God and with each other could help all of us flourish.

Over time, progressive Christians became some of the most prominent and public leaders in a larger nationwide movement of social change. The Social Gospel movement sought to apply Christian ethics to real-world issues like poverty, labor rights, housing, and education. It said: our faith is about how we care for children. How we protect workers. How we challenge unjust systems.

As industrialization saw huge growth in cities across the country in the late 19th century and early 20th century, especially in the Midwest, the Social Gospel movement was hugely successful in stopping the development of monopolies and speaking out for the everyday workers and rights of children. They planted values of caring for the whole and building a system where all can benefit. (This was, sadly, only true for those who were white.)

My family history

My grandfather, born in 1896 in Illinois, came of age during the height of this movement when progressive ideals were preached in churches and the town square. As the son of the conductor of the Illinois Central Railroad and a recent Irish immigrant mother, my grandfather was steeped in the ideas of progress and possibility. Every Sunday he was taught to make a practical connection between his faith and his political and social responsibility.

This progressive movement set off a cascade of larger systemic changes in our nation that improved labor rights, working conditions, voting for women, and educational institutions.

Progress was unevenly shared

At the same time, the progress and development were unevenly shared across the population. Racial inequality became further entrenched as cities and states passed Jim Crow laws. While factory conditions improved, innovation and technological advancements meant that the demand for raw materials only increased, especially for copper, which was beginning to decline in production in the US.

This laid the groundwork for the development of an economic imperialistic system around the world, starting in Central and South America where corporations could pay lower wages and face fewer safety regulations. Corporations took advantage of the fragile political climate to invest in the development of factories, railroads, and mines to harvest raw materials — often at great cost to the local communities.

In the early 20th century, the Anaconda Copper Mine Company opened the largest open copper mine in the world in the northern plains of Chile in a town called Chuquicamata.

The company didn’t just build a mine. It built a whole town, complete with schools, homes, churches, and grocery stores. The best housing and jobs were reserved for foreign workers. Chilean families lived with less — less opportunity, fewer rights, and working conditions that were often inhumane.

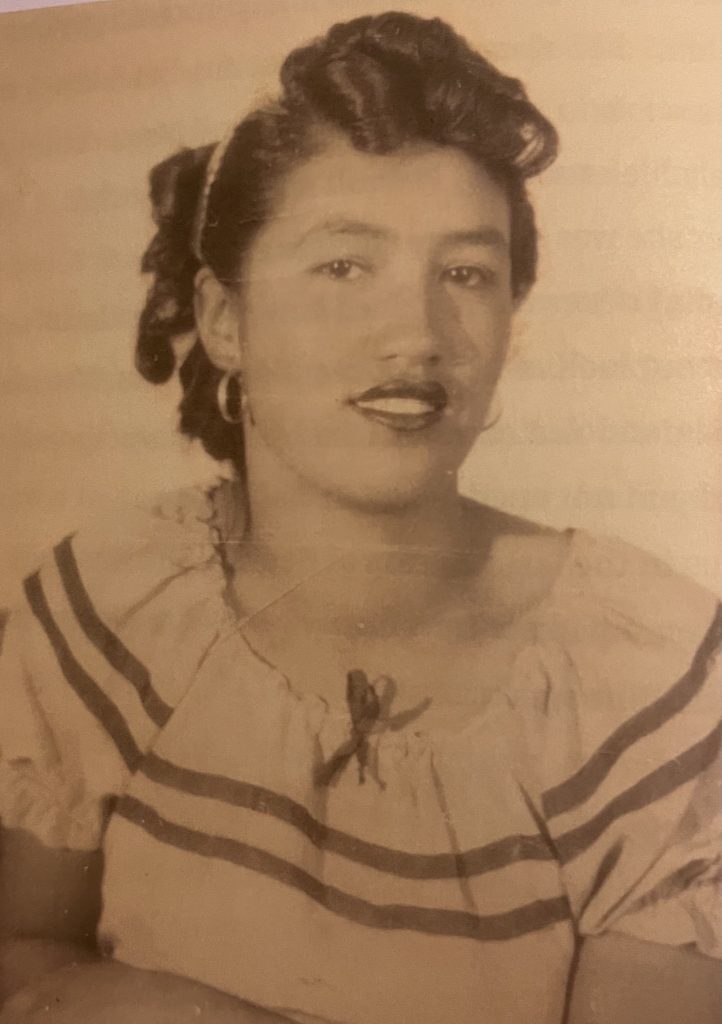

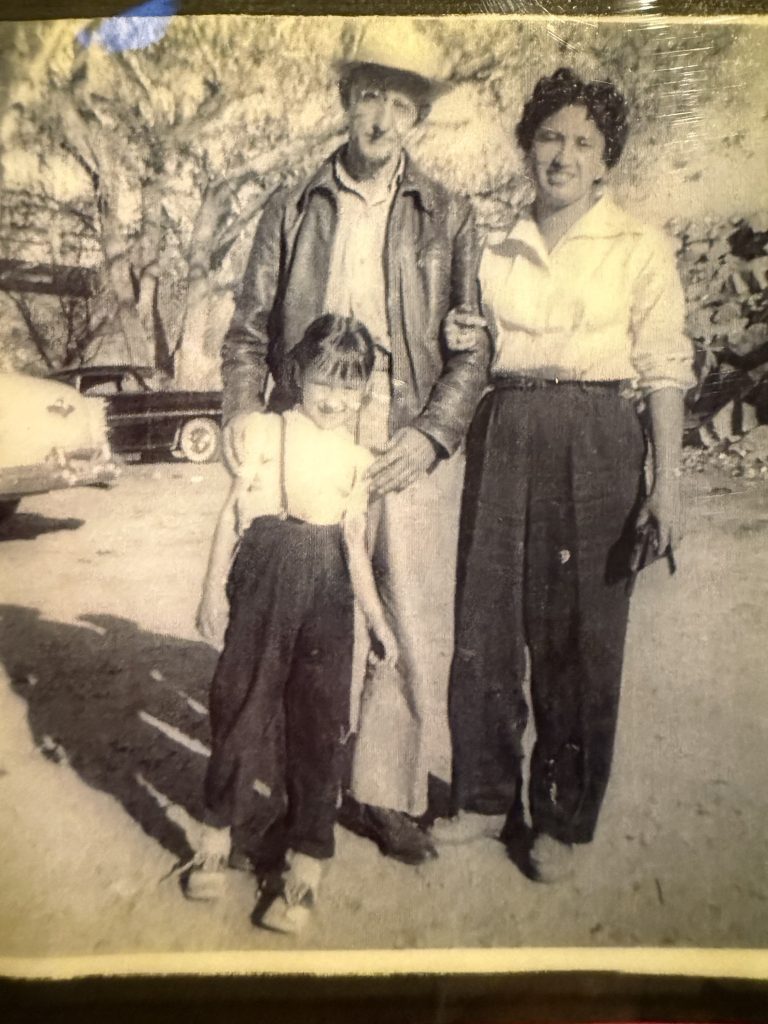

Among those workers to move to Chuquicamata was my great grandfather, a recent Chinese immigrant, who came in the early 1930s and ran a grocery store. My grandmother grew up in this town, assisting her father at the store and helping care for her younger brother and sister.

In the late 1940s, my grandfather was hired by the Anaconda Copper Company as an electrical engineer and was stationed in Chuquicamata. It’s there that he met my grandmother.

Though many investors outside of Chile, especially companies like Anaconda, were profiting greatly from the extractions of copper, very little of this profit stayed within Chile. Living and working conditions for locals were harsh and opportunities were scarce — so much so that my grandmother saw what her future would look like if she were to stay in this mining town.

She said yes to the marriage proposal of a kind man who was 34 years older than she, not because she loved him, but because she saw a way out — an opportunity for her and her younger sister, and the family she would one day have, starting with my mother.

Progress and change were the driving forces that brought my grandparents together. It was also complicated.

Those early progressive ideals that my grandfather had been steeped in deeply influenced how he chose to raise his daughter.

“You can do anything those boys can do. Don’t ever let them tell you different,” he would say to her over the years.

(You won’t be surprised to know that my mother repeated this sentiment multiple times as I was growing up).

Leaning into the complexity of our own lived experiences

This week, digging into the history of the progressive movement, its theology, its contributions to society, and its massive blind spots, I am trying to hold that invitation to see with more of myself. To stay with the complexity, the nuances, and to ask about how this lens can help me stay more present to the challenges of our current moment. Leaning into the complexity of our own lived experiences, our histories, our stories, is a real way of knowing something deeper about the world and about how it is we are to respond.

Real progress is never simple and straightforward. My grandmother only returned to Chile once after coming to the States. While she was able to build a life for her children that she, herself, could have never imagined as a child, it wasn’t without cost and struggle. Most of my grandmother’s extended family never left this area of Chile. The area where they live now continues to be plagued by environmental degradation from the mine, even though it closed over 50 years ago.

The progressive Christian lens invites us to stay in this place of complexity — where progress and change open the doors to liberation for some and injustice and inequity for others.

What does it look like for us to keep allowing our faith to help us ask new questions about the present, about what is possible, and about how we consider the real costs of the choices we are making every day?

How might the lens of progressivism help us resist simple answers and instead embrace a deeper kind of faith — one that asks us to stay with the tension, listen longer, and love more bravely?

And what might it look like for each of us, in our own way, to join the ongoing work of creating a world where every person — not just the privileged few — can flourish?

Look forward to being together on Sunday!

With love and curiosity,

Pastor April

The Rev. April Blaine

Lead Pastor